I am pleased to announce that our Cleveland Teaching Collaborative Chalk Talk podcast is live!

Visit podcast.cleteaching.org to listen to our first episode on Makerspace teaching and learning.

Exploring gendered, protest and digital spaces

I am pleased to announce that our Cleveland Teaching Collaborative Chalk Talk podcast is live!

Visit podcast.cleteaching.org to listen to our first episode on Makerspace teaching and learning.

Teams, like Blackboard or Google Classroom, is a platform instructors can use as a learning management system (LMS). Unlike Google Apps which are little to no cost to students at any institution, Teams is most practical as an LMS option when your campus or system already subscribes to Microsoft 365 products.

Teams is appropriate for use in remote, hybrid, flipped, or in-person courses. It works well with a range of class sizes and student feedback suggests that the availability of a user-friendly Teams mobile app increases student engagement with the platform, especially for interactive and searchable discussions.

As a higher education level instructor, I have used Teams in both in-person and remote courses. It is particularly useful for fostering community among students. Here is a quick guide to setting up your own classroom in Teams.

Use your CSU credentials to log in to Microsoft Teams. You may also access it through the CSU Webmail. To do so, sign into your email via MyCSU (https://mycsu.csuohio.edu/). When in your CSU email inbox, click on the square (made up of 9 small squares) in the upper left corner and choose Teams from the dropdown menu of resources. You will see our course team listed.

Sign into your institution’s Teams platform or visit teams.microsoft.com

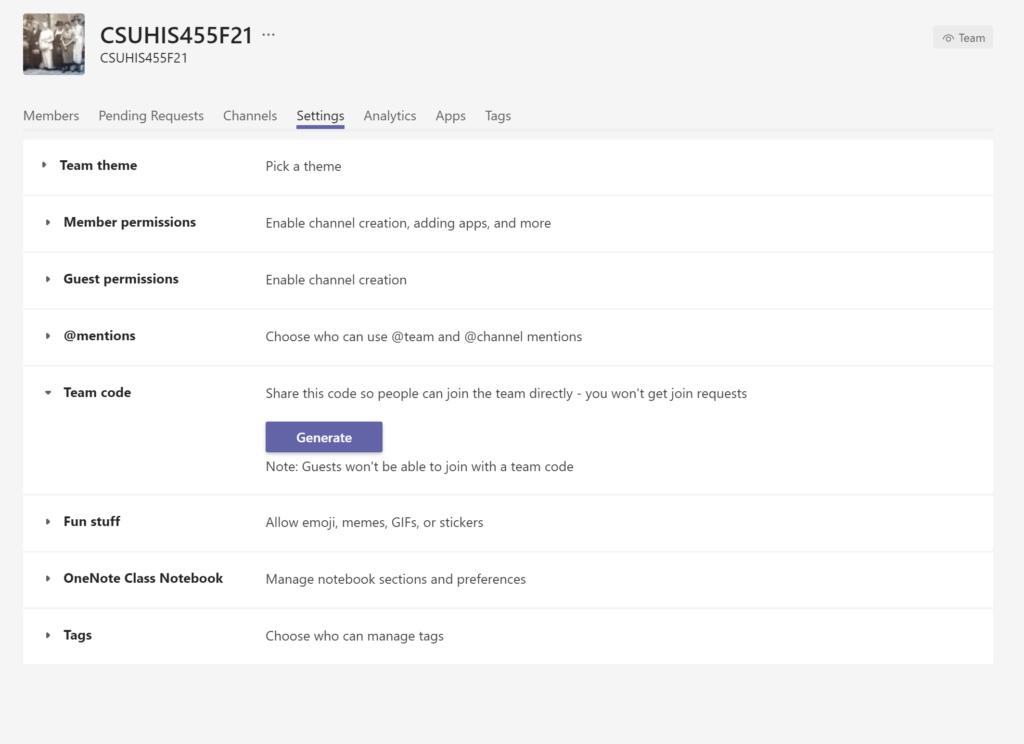

If you plan to use Teams in tandem with other LMS or platforms, or want students to add themselves to the Team, you can set a Team Code. Go to the three dots next to your Team name and choose “Manage Team.” Under “Settings” > “Team Code” you can generate a unique code for your Team to share with your student via email or LMS. Typically only students at your institution can add themselves to the Team. All guests must be added by the Team instructor.

The “Class” Teams type comes populated with tabs for Files (Sharepoint/OneDrive), Class Notebook (OneNote), Assignments, and Grades. You will not be able to remove these tabs from your Team. You can, however, add tabs (see adding Apps)

The “Class Materials” folder is read only. This is the place to put your syllabus, course readings, etc. Students will be able to view your documents, but not edit them. Once you set it up, it will be available under the “Files” tab.

Each Teams Class is linked to OneNote. You must set up the Class Notebook to activate the connection. You may choose to set up a blank notebook or integrate an existing OneNote notebook into the course.

The Class Notebook can serve as a hub for handouts, student work, etc. Students each have their own private notebook space that only the instructor and individual student can see. This can be a useful space for personalized and private feedback for students.

Add a Blackboard Login Tab

1. Click on “Add new Tab”

2. Select “Website.”

3. Provide the name and URL of the site. (Pro-Tip: Open the Blackboard Login page in an incognito or private browser window and then copy paste the URL to the login page)

Add a Syllabus Tab

1. Open the Files Tab and upload the Syllabus file in PDF (or Word) format if you have not done so already.

3. In the General Channel click on “Add New Tab”

4. Select the matching format PDF or Word file from the tiles.

5. Fill in the file name for your tab in the popup box.

6. Select the file you wish to populate the tab.

Add a Course Website or Ebook

1. Click on “Add new Tab”

2. Select “Website.”

3. Provide the name and URL of the site.

One of the advantages to Microsoft Teams as a Classroom space is that it provides a single platform that links multiple apps. Common interactive educational apps like Flipgrid, Miro, NearPod and Pear Deck are can be integrated into the Team as tabs so students don’t have to leave the classroom and juggle multiple logins.

Instructors can administer assignments in the Teams Classroom. They will be linked to the “Grades” tab and can be graded in app. If you are using Blackboard or another LMS for your gradebook, these grades can be exported as a csv file.

If you use integrated Teams assignments the “Grades” tab will populate with assignments and allow you to comment.

You can also ignore the Grades tab and use the gradebook of your choice (Blackboard for example) When I surveyed students at the start of my courses, they preferred discussions in Teams and grading in Blackboard.

You can also interact with students individually or in groups in the “Chat” section of Teams (see left general menu). This means they can message you on the app or in the web version and you can respond to individual questions privately but in the context of the Teams platform

I also use MS Teams to set up my remote office space. This space is team type “Other” and open to all Teams users at my organization (CSU). That way any one in my campus community can “stop by.”

Visit my office: https://bit.ly/RoseOffice

During emergency remote learning all department functions moved online as well. That included major advising. As a result, we set up a remote advising center using the Class type in Teams. Using the Class type provided us with the default Class Notebook . The individual notebooks became the private advising “file folders” for each student.

Our graduate assistants staff the History Resource Center. They transformed this student resource for assignment assistance and writing help to remote environment using Microsoft Teams PLC type.

Video: Setting up Your Classroom or Office in Microsoft Teams

CSU Teams Resource Page: https://www.csuohio.edu/messaging-services/teams

Microsoft Teams CSU Test Classroom: http://bit.ly/CSUTeamsTestClassroom

Introduction to Microsoft Teams: https://education.microsoft.com/en-us/resource/d5b62e3e

As we considered the transition to emergency remote learning in Spring 2020, I turned to Twitter and especially to new connections I made at the Winter Institute for Digital Humanities at NYU Abu Dhabi earlier this year. Among the many links and suggestions shared in that moment, the NYU Shanghai Digital Teaching Toolkit stood out as a model for reflecting on remote teaching and learning.

CSU’s semester drew to a close and I realized that it was our turn to reflect on a semester of emergency remote learning and prepare for a future which would inevitably include remote and hybrid teaching and learning. I’m so grateful for Dr. Molly Buckley-Marudas, associate professor of Teacher Education and Faculty in Residence at the Campus International High School, who shared my vision of creating a community of educators from Pre-K to higher education who would reflect on the semester, prepare for the fall, and most importantly support one another as we navigate this new territory in education.

Thanks to support from our departments and colleges, the Cleveland Teaching Collaborative (http://cleteaching.org/) was created in May 2020. Our first cohort is an interdisciplinary group of educators from across Northeast Ohio. Each participant wrote a case study reflection on their experiences in spring 2020 and met with a focus group of 4-6 people to discuss challenges, successes, and plans for the future. We hope to see this community grow as we continue to collaborate in the coming year.

One of the products of the collaborative is a resource referatory (http://referatory.cleteaching.org/) geared toward Cleveland educators and open to all audiences. We hope that this will serve as a crowdsourced toolkit for educators as we move into various stages of teaching and learning in Fall 2020.

(This post originally appeared on the Protest Spaces Research Network Blog)

In February 2014, Jared Donnelly and I sat in the audience at a conference in Lisbon, Portugal – “Resisting War in the Twentieth Century” – and wondered what would happen if historians started to consider space more systematically in protest movement research. What would a map of all the protest events we studied across dozens of archives look like? What could we learn from it? The Protest Spaces mapping pilot project was born.

Four years later, it is clear that the question of space in protest movement research is much broader than mapping. The Protest Spaces Mapping Project will remain a cornerstone of this interdisciplinary network; the first of what I hope will be many projects to come. I envision the network as a place for participants to discuss potential projects, collaborate, and share skills, regardless of their primary projects. In the case of peace movement research, Norwegian sociologist Johan Galtung argues “the peace researcher has no fatherland.”[1] Not only are many activist networks transnational, researching activists and activism is inherently a transnational endeavor. The digital turn enables us to make the analysis and dissemination of protest movement research a transnational effort as well.

This is a call to researchers, archivists, developers, activists, and students of any discipline interested in the intersection of spatial humanities, digital humanities, and protest movement research.

The Protest Spaces Research Network will connect individuals across disciplinary, national, and professional boundaries to create a research community dedicated to exploring the spaces of protest. One of the main goals of this network is to conceptualize the meanings of “space” for protest research, ranging from physical locations of protest events to virtual spaces and archival spaces.

The first task of the Protest Spaces Research Network will be to organize a conference to assess the current state of transnational protest movement research and foster connections between participants with existing or planned projects. I will post all updates on the conference on the network site and on Twitter @protestspaces.

Please complete this form if you would like to join or receive updates from the Protest Spaces Research Network. Contact me at shelley.rose@csuohio.edu with any questions or inquiries.

References:

The German Studies Association conference is well underway – you can follow the #gsa2018 and #gsadh to keep up with all the exciting panels.

I will update this post with a conference debrief, but for now here is a link to my own slides on digital humanities and pedagogy. I have included links to syllabi, assignments, and rubrics that I use to teach digital methods at Cleveland State University. Feel free to contact me with any questions!

UPDATE: You can read more about the digital humanities research seminar here.

*This post originally appeared on the Peace & Change Blog on July 23, 2018.

For a couple years now, department colleagues have encouraged me to find a space where my research in protest movements and gender intersected with my interests in digital humanities and pedagogy. The product of those conversations is a course I offered in Fall 2017, “The Politics of Peace and Gender.” Excited by the possibility of sharing my passion for these fields with my students, I had three main goals:

Here is the description from the syllabus:

This course investigates perceptions of peace and gender in politics, drawing on insights from international relations and human rights history to study gendered conceptualizations of peace as “feminine” and assumptions that militarism and war are historically “masculine.” The chronology of the course begins with Bertha von Suttner’s pacifist novel Lay Down your Arms! (1889) and ends in the present day. Through primary and secondary research, students will evaluate the importance of gender analysis in the study of war and its opponents. In particular, this course emphasizes the various roles of men and women participating in protest events and the spaces they choose occupy. The course fosters a transnational perspective, highlighting different historical and geographical contexts such as 19th– century nationalism in Europe, the experience and aftermath of World War I, international debates around disarmament including nuclear disarmament, gendered violence during the dirty wars in Latin America, and more recent mass transnational protest events such as the Women’s March on Washington and the Occupy Movement.

“Politics of Peace and Gender” enrolled 13 undergraduates, 2 graduate students, and 3 “Project 60” students. This was one of the most academically diverse groups of students I have ever taught in an upper-level history course. Not only did students range in technical ability, they came to the course from various majors and programs including Asian Studies, Black Studies, Education, English, Gender and Women’s Studies, History, Political Science, Psychology, and Social Studies. Early in the semester, I adopted the strategy of pulling key terms from our daily readings and posting them on the course chat (in this case we used university-supported Microsoft Teams). I also wrote the term list on the whiteboard in the classroom before each discussion. While I took attendance, students could walk to the board and put a checkmark next to the term(s) they wanted to be sure we reviewed during our session. This turned out to be a valuable exercise due to the interdisciplinary nature of both the materials and students. For instance, a term like “thick description” is familiar to history and anthropology students, but often unfamiliar to psychologists and others in the room.

In order to emphasize transferable skills, I approached this course as a digital methods course where students created an Omeka exhibit on a protest event of their choice as a final project. I drew heavily on my experience with project-based learning (PBL) and used the student-created exhibits from the Colored Conventions Project as a model to design a series of weekly skill-based labs that provided a foundation for the final project. I thought carefully about the branding for this course, and ultimately decided to use the word “lab” for work sessions. While the idea of a laboratory is borrowed from STEM fields, I use it to emphasize that these sessions are a time to experiment with digital methods. I made a conscious effort to convey to my students that it was ok to stumble, or even fail, when creating digital content – just like many scientists.

I love that digital humanities methods and projects challenge the assumption among academics and students that all assignments must represent a “finished” product. I stress to my students that it is fine to have work in progress. After all, academics present their own work at conferences before polishing ideas into an article or book. This is the reason why I grade labs separately from the final project (which deviates slightly from the traditional PBL model). My goal is to provide students with space to grow and, I hope, to be more courageous in their final project. Students were able to use network diagrams, maps, and other elements from their labs, but they were not required to use all of them in order to preserve the element of choice that is considered key to PBL.

Project-based learning calls for a public product for the final projects. The “Politics of Peace and Gender,” student exhibits are posted on a public Omeka site. All students were required to present their exhibit at the DigitalCSU working group research showcase in our library at the end of the semester. At the time, I hosted the site as a subdomain on my own website. I am now in the process of working with the CSU library to archive this site on their servers to ensure sustainability and to link it more clearly to the university’s Bepress site, EngagedScholarship @ CSU. Students were evaluated according to this rubric.

As a special topics course “Politics of Peace and Gender” was cross-listed for both undergraduate and M.A. students. Each M.A. student completed the Omeka exhibit and also wrote an academic blog post. You can read Katherine Behnke’s post on Bernadette Devlin on the Peace & Change blog. It’s an excellent example of how research for the digital exhibit revealed a significant gap in the historiography of a well-known protest event.

Student exhibits covered topics from The 1919 May 4th Incident in China to Bloody Sunday in Northern Ireland. You can view them all on http://csuhisppg.shelleyrose.org/.

Note: this is a cross-post from Social Studies @ CSU.

The Cleveland International Film Festival is here! We are keeping up with the tradition to look through the schedule and see which films will be interesting and useful for History and Social Studies teachers. Every year key themes emerge from this list. This year’s dominant themes are education, geography, gender, and LGBQT+.

Let’s get the #CIFF42 chat started in the comments and on Twitter @SocstudiesatCSU!

Current CSU students: You can present your CSU ID for 2 vouchers for the CIFF in SC 319 (Student Life Office). Also visit https://www.csuohio.edu/class/film/csu-day for other ways to see films for free or discounted rates.

Disclaimer and Navigation: This is not an exhaustive list of all films at the festival. I have organized it into loose categories of US, World, and Europe.

Special thanks to Drs. Kelly Wrenhaven and Karen Sotiropoulos for assisting with this list!

306 HOLLYWOOD

Year: 2018

Country: USA, HUNGARY

Run Time: 94 minutes

URL: https://www.clevelandfilm.org/films/2018/306-hollywood

Topics: US, Cultural History

ACORN AND THE FIRESTORM

Year: 2017

Country: USA

Run Time: 84 minutes

URL: https://www.clevelandfilm.org/films/2018/acorn-and-the-firestorm

Topics: American Government, Contemporary Issues

AFTER LOUIE

Year: 2017

Country: USA

Run Time: 100 minutes

URL: https://www.clevelandfilm.org/films/2018/after-louie

Topics: Contemporary Issues, LGBQT+

AFTER SOLITARY

Year: 2017

Country: USA

Run Time: 9 minutes

URL: https://www.clevelandfilm.org/films/2018/after-solitary

Topics: Sociology, Contemporary Issues

ALASKA IS A DRAG

Year: 2017

Country: USA

Run Time: 89 minutes

URL: https://www.clevelandfilm.org/films/2018/alaska-is-a-drag

Topics: Contemporary Issues, LGBQT+

BAD REPUTATION

Year: 2017

Country: USA

Run Time: 92 minutes

URL: https://www.clevelandfilm.org/films/2018/bad-reputation

Topics: Music history, Joan Jett, American history

BISBEE ’17

Year: 2017

Country: USA

Run Time: 118 minutes

URL: https://www.clevelandfilm.org/films/2018/bisbee-17

Topics: immigration, Arizona, Contemporary Issues, politics of memory, labor history

BOOM FOR REAL: THE LATE TEENAGE YEARS OF JEAN-MICHEL BASQUIAT

Year: 2017

Country: USA

Run Time: 78 minutes

URL: https://www.clevelandfilm.org/films/2018/boom-for-real-the-late-teenage-years-of-jean-michel-basquiat

Topics: New York City, art, Basquiat, urban history

BURDEN OF GENIUS

Year: 2017

Country: USA

Run Time: 88 minutes

URL: https://www.clevelandfilm.org/films/2018/burden-of-genius

Topics: technology, history of medicine, ethics

MANRY AT SEA ~ IN THE WAKE OF A DREAM

Year: 2017

Country: USA

Run Time: 93 minutes

URL: https://www.clevelandfilm.org/films/2018/manry-at-sea-in-the-wake-of-a-dream

Topics: Cleveland, Sailing, Willowick

DARK MONEY

Year: 2018

Country: USA

Run Time: 98 minutes

URL: https://www.clevelandfilm.org/films/2018/dark-money

Topics: American government, contemporary issues, politics

AN ACT OF DEFIANCE

Country: NETHERLANDS

Directed By: Jean van de Velde

Running Time: 123 Minutes

URL: https://www.clevelandfilm.org/films/2018/an-act-of-defiance

Topics: apartheid, racism, South African history

ALI’s WEDDING

Country: AUSTRALIA

Directed By: Jeffrey Walker

Running Time: 110 Minutes

URL: https://www.clevelandfilm.org/films/2018/alis-wedding

Topics: culture, cultural conflict, family, religion, migration

AKASHI

Year: 2017

Country: CANADA

Run Time: 10 minutes

URL: https://www.clevelandfilm.org/films/2018/akashi

Topics: Geography, Japan, Contemporary Issues, migration

ASK THE SEXPERT

Year: 2017

Country: USA

Run Time: 83 minutes

https://www.clevelandfilm.org/films/2018/ask-the-sexpert

Topics: India, gender, contemporary issues

ANOTE’S ARK

Year: 2018

Country: CANADA

Run Time: 77 minutes

URL: https://www.clevelandfilm.org/films/2018/anotes-ark

Topics: Geography, climate change, migration

BEFORE SUMMER ENDS (Avant la fin de l’ete)

Year: 2017

Country: SWITZERLAND, FRANCE

Run Time: 80 minutes

https://www.clevelandfilm.org/films/2018/before-summer-ends

Topics: Migration, Middle East, France, geography

BORG VS. MCENROE

Year: 2017

Country: SWEDEN, DENMARK, FINLAND

Run Time: 107 minutes

URL: https://www.clevelandfilm.org/films/2018/borg-vs-mcenroe

Topics: sports history, media, mental health

BURKINABÈ RISING – THE ART OF RESISTANCE IN BURKINA FASO

Year: 2017

Country: BURKINA FASO

Run Time: 72 minutes

URL: https://www.clevelandfilm.org/films/2018/burkinab-rising–the-art-of-resistance-in-burkina-faso

Topics: Burkina Faso, Africa,nonviolence

ON HER SHOULDERS

Year: 2018

Country: USA

Run Time: 94 minutes

URL: https://www.clevelandfilm.org/films/2018/on-her-shoulders

Topics: Middle East, education, gender, human rights

THE NEW FIRE

Year: 2017

Country: USA

Run Time: 84 minutes

URL: https://www.clevelandfilm.org/films/2018/the-new-fire

Topics: Geography, climate change, global warming, technology, contemporary issues

THE SEEN AND UNSEEN

Year: 2017

Country: INDONESIA

Run Time: 86 minutes

URL: https://www.clevelandfilm.org/films/2018/the-seen-and-unseen

Topics: Indonesia, world history, geography

TAKE LIGHT

Country: CANADA

DIRECTED BY: SHASHA NAKHAI

RUNNING TIME: 78 MINUTES

URL: https://www.clevelandfilm.org/films/2018/take-light

Topics: Nigeria, Africa, geography

100 WOMEN I KNOW

Year: 2017

Country: UNITED KINGDOM

Run Time: 13 minutes

URL: https://www.clevelandfilm.org/films/2018/100-women-i-know

Topics: Sexual assault, women’s & gender studies, contemporary issues

1745

Country: UNITED KINGDOM

Directed By: Gordon Napier

Running Time: 18 Minutes

URL: https://www.clevelandfilm.org/films/2018/1745

Topics: slavery, racism, British history, empire

THE ART OF LOVING (Sztuka Kochania)

Year: 2017

Country: POLAND

Run Time: 120 minutes

https://www.clevelandfilm.org/films/2018/the-art-of-loving

Topics: Poland, Europe, Cold War, women’s and gender studies

BAREFOOT (Po strnisti bos)

Year: 2017

Country: CZECHIA

Run Time: 104 minutes

https://www.clevelandfilm.org/films/2018/barefoot

Topics: World War II, Prague

MADEMOISELLE PARADIS (Licht)

Year: 2017

Country: AUSTRIA, GERMANY

Run Time: 97 minutes

URL: https://www.clevelandfilm.org/films/2018/mademoiselle-paradis

Topics: Austria, 18th century history, Europe

MAZE

Year: 2017

Country: IRELAND

Run Time: 93 minutes

URL: https://www.clevelandfilm.org/films/2018/maze

Topics: Northern Ireland, IRA

THE OTHER SIDE OF EVERYTHING (Druga strana svega)

Year: 2017

Country: SERBIA, FRANCE, QATAR

Run Time: 104 minutes

URL: https://www.clevelandfilm.org/films/2018/the-other-side-of-everything

Topics: Serbia, communism, Balkans, geography

SILVANA

Year: 2017

Country: SWEDEN

Run Time: 91 minutes

URL:https://www.clevelandfilm.org/films/2018/silvana

Topics: rap, hip-hop, Sweden, gender, LGBQT+

WESTWOOD: PUNK, ICON, ACTIVIST

Year: 2017

Country: UNITED KINGDOM

Run Time: 78 minutes

URL: https://www.clevelandfilm.org/films/2018/westwood-punk-icon-activist

Topics: activism, United Kingdom, New York City, fashion

WHAT WILL PEOPLE SAY (Hva vil folk si)

Year: 2018

Country: NORWAY, GERMANY, SWEDEN

Run Time: 106 minutes

URL: https://www.clevelandfilm.org/films/2018/what-will-people-say

Topics: migration, Europe, Norway, Pakistan, geography

School/Education Theme

6 WEEKS TO MOTHER’S DAY

Year: 2017

Country: USA, THAILAND

Run Time: 92 minutes

https://www.clevelandfilm.org/films/2018/6-weeks-to-mothers-day

Topics: Thailand, Contemporary Issues, Geography

ADVENTURES IN PUBLIC SCHOOL

Country: CANADA

Directed By: Kyle Rideout

Running Time: 86 Minutes

URL: https://www.clevelandfilm.org/films/2018/adventures-in-public-school

Topics: Teens, coming-of-age, public school, education

AND THEN I GO

Country: USA

Directed By: Vincent Grashaw

Running Time: 99 Minutes

URL: https://www.clevelandfilm.org/films/2018/and-then-i-go

Topics: Teens, coming-of-age, school violence, education

BLUE MY MIND

Year: 2017

Country: SWITZERLAND

Run Time: 98 minutes

Topics: Teens, coming-of-age, fantasy, women’s studies

BREAKING THE BEE

Year: 2018

Country: USA

Run Time: 96 minutes

URL: https://www.clevelandfilm.org/films/2018/breaking-the-bee

Topics: education, Indian-American community

BREAKING THE GRADE

Year: 2017

Country: USA

Run Time: 21 minutes

URL: https://www.clevelandfilm.org/films/2018/breaking-the-grade

Topics: education, Columbus, Ohio

FAIL STATE

Year: 2017

Country: USA

Run Time: 94 minutes

URL: https://www.clevelandfilm.org/films/2018/fail-state

Topics: for-profit colleges, higher education

SCIENCE FAIR

Year: 2018

Country: USA

Run Time: 90 minutes

Url: https://www.clevelandfilm.org/films/2018/science-fair

Topics: STEM, education

In 2016, I sat down to evaluate digital media sites that focus on women’s and gender history. I soon realized there is no systematic way to search for digital projects. They are not cataloged by libraries or databases with the same methods use for traditional print publications and journals. I faced the problem of gathering information on a field that did not have a collective archival or institutional footprint.

This is the moment when this crowd-sourced list of Women’s and Gender History digital projects was born. It is an effort to gather information on digital media in the field of women’s and gender history in one central space. Women’s and gender scholars often create close links with organizations and individuals beyond the academy. These projects are both a testament to those collaborations and nod to the reality that digital content is generally accessible to anyone with an internet connection. These project create a sense of community among users/readers even beyond the control of the project creators.

You might be wondering about the tech behind the list. It is a Google document that is set to “anyone with the link can edit.” I uploaded that link to the Google URL shortener in order to get some basic analytics and shared it widely on Twitter and other social media. There are many ways to crowd-source information like this, but I wanted to reach a wide audience and encourage participation, so I kept the tech level basic. I have often considered transferring the data into a content management system (CMS), but at this point in my career it is not a priority.

This list has grown over the course of my project, and I think it’s time to share it in this space as well. Feel free to add to list to spread the word about your own projects, learn about the growing field of digital media in women’s and gender history, and foster community among the diverse audience for such projects. I’d love to hear your feedback in the comments.

Note: The original post appeared on the Peace & Change blog.

It’s not where you think it is.

Like many, I have been following the protests against the Dakota Access Pipeline (DAPL) and the establishment of the Sacred Stone Camp in April 2016. (see this helpful timeline from Mother Jones) When I signed into Facebook this morning, my feed was flooded with friends and colleagues checking in at Standing Rock, ND.

My first thought: I’ve definitely missed something big.

It soon became clear that my contacts had not all traveled to North Dakota overnight. So what changed in the movement? The exact origins of this virtual campaign remain unclear, but Kim LaCapria of Snopes.com reports that it did not originate with the Sacred Stone Camp. Regardless of the campaign’s origins, No-DAPL supporters checking-in on Facebook occupy the growing virtual space of Standing Rock: harnessing the power of social media, and bringing the physical confrontation to the digital realm. Here I again ask the question: Where is Standing Rock?

The Standing Rock movement is intricately tied to both the physical location of the Sacred Stone Camp and virtual locations for protest on social media, including the Standing Rock Facebook page and #NoDAPL tag. As an historian interested in space as a lens into protest movement histories (ok, borderline obsessed), this is an excellent example of how protests and the spaces they occupy are intimately linked, and most often, deliberately chosen. While a single blog post cannot provide a thorough analysis of protest spaces, here I offer three reasons why the Standing Rock locations matter.

1. Location-based Protest and Communities of Practice

Shared physical spaces brings individuals together around a common issue and establishes common narratives in ways that cannot be discounted in the study of protest movements. Spatial proximity fosters a heightened sense of community, profoundly impacting individual activists long after they leave the protest site. Huffington Post’s Katie Scarlett Brandt describes this feeling well in her recent article “I am a White Person Who Went to Standing Rock. This is What I Learned.” Brandt’s thick description of sleeping outside at the camp, waking up to the mundane sounds of her fellow activists starting their day, and being embedded in the routine of the movement all supports the role of shared space in the creation of activist communities of practice. As a scholar, I rely on Sally McConnell-Ginet and Penelope Eckert’s definition of communities of practice as “an aggregate of people who come together around mutual engagement in an endeavor. Ways of doing things, ways of talking, beliefs, values and power relations- in short, practices- emerge in the course of this mutual endeavor.” [1] What is most important about communities of practice, is that their boundaries remain undefined, limited only by the scope of interaction and the spaces occupied by individual members. Transferred as a lens into the No DAPL protests, the physical space of the Sacred Stone Camp brings individuals together around a common issue and establishes common narratives for protest. This type of space-based solidarity can also be seen in the #NoTAV movement as documented by political scientists Donatella della Porta, Maria Fabbri and Gianni Piazza.[2]

2. Isn’t this just hashtag activism?

Not exactly. Standing Rock is a critical moment for reexamining the role of social media in protest movements. As in the Occupy movement and the Arab Spring protests, social media outlets provide a key means of communication for activists to find the physical locations of the movement. In fact, social media posts were among the first catalysts for such a diverse group of Native Americans and their supporters to gather in North Dakota. (See this September 2016 article by Jack Healy). Yet even earlier today I read social media posts questioning the real-world impact of checking-in at Standing Rock. The general conclusion seems to be that it helps just to “do something” to raise awareness.

These place-based solidarity posts on Facebook beginning on October 30 are what make the Standing Rock case different, and marks a new direction in the relationship between social media and protest events. Each “check- in” at Standing Rock represents an exercise of power from a growing activist community of practice in the social media world. This is not a standalone hashtag, social media activists checked-in with the belief that they could disrupt the perceived “geo-targeting” power of law enforcement and security forces over No-DAPL activists. In short, virtual interventions might physically protect activists. Those occupying “virtual” Standing Rock, regardless of the actual impact on law enforcement, are expanding the community of practice, drawn to sense of solidarity fostered by Standing Rock as a physical protest space, and compelling networks of virtual activists to create a digital extension of that location.

3. Is “virtual” Standing Rock still Standing Rock?

Standing Rock is not just a space for protest, it is a place. Geographers understand place as space inscribed with meaning. Standing Rock has a long place history, grounded in the struggles between the Native Americans and the US government. As of 2016, it also has a place history as a site of protest against the DAPL. In the last 24 hours, I argue, “virtual” Standing Rock has also become a place. It is intimately tied to the physical space in North Dakota, and yet stands on its own as a virtual space, occupied for a specific purpose by a diverse group of people coming together around a common cause. It is not sponsored by any established organization, but formed organically and has had 198,267 visits by the time of this writing. Historian David Glassberg argues that spaces anchor individuals in their “sense of history” and a common past. [3] In this case, the occupation of both physical and virtual Standing Rock has engaged individuals in an activist community of practice and the creation of place through protest.

References:

*This is a cross-post with Social Studies @ CSU*

The Cleveland International Film Festival is around the corner! I am keeping up with the tradition to look through the schedule and see which films will be interesting and useful for History and Social Studies teachers. Every year key themes emerge from this list. Perhaps not surprising, this year’s dominant themes are migration, climate change, and race.

Let’s get the #CIFF40 #sschat started in the comments and on Twitter @SocstudiesatCSU!

Current CSU Social Studies students: contact me at shelley.rose@csuohio.edu if you plan to see a film on the list. I have a limited number of vouchers available for students thanks to the CSU Office of Engagement.

Current College Students: Present your current student ID for free admission. See http://www.clevelandfilm.org/college for more details.

Disclaimer and Navigation: This is not an exhaustive list of all films at the festival. I have organized it into loose categories of US, World, and Europe

US

2nd Life

Year: 2015

Country: USA

Run Time: 8 minutes

http://www.clevelandfilm.org/films/2016/2nd-life

Topic: Migration

May 4th: Our Place in History

Year: 2015

Country: USA

Run Time: 26 minutes

http://www.clevelandfilm.org/films/2016/may-4-our-place-in-history

Topic: Kent State, Protest

BELIEVELAND (featuring CSU’s own Mark Souther)

Year: 2016

Country: USA

Run Time: 77 minutes

http://www.clevelandfilm.org/films/2016/believeland

Topics: Cleveland

World

SONITA

Year: 2015

Country: GERMANY, IRAN, SWITZERLAND

Run Time: 90 minutes

http://www.clevelandfilm.org/films/2016/sonita

Topics: Afghanistan, Iran, arranged marriage, migration

YALLAH! UNDERGROUND

Year: 2015

Country: CZECH REPUBLIC, GERMANY, UNITED KINGDOM, EGYPT, CANADA, USA

Run Time: 85 minutes

http://www.clevelandfilm.org/films/2016/yallah-underground

Topics: Arab Spring, Music

HOW TO LET GO OF THE WORLD AND LOVE ALL THE THINGS CLIMATE CAN’T CHANGE

Year: 2016

Country: USA, AUSTRALIA, CHINA, ECUADOR, ICELAND, PERU, SAMOA, VANUATU, ZAMBIA

Run Time: 125 minutes

http://www.clevelandfilm.org/films/2016/how-to-let-go-of-the-world-and-love-all-the-things-climate-cant-change

Topics: Climate Change, Geography

WALLS (Muros)

Year: 2015

Country: SPAIN, MOROCCO, USA, MEXICO, SOUTH AFRICA, ZIMBABWE, PALESTINE

Run Time: 80 minutes

http://www.clevelandfilm.org/films/2016/walls

Topics: Borderlands, Geography

Europe

1944

Year: 2015

Country: ESTONIA, FINLAND

Run Time: 100 minutes

http://www.clevelandfilm.org/films/2016/1944

Topics: World War II, Eastern Europe

Morris From America

Year: 2016

Country: USA, GERMANY

Run Time: 89 minutes

http://www.clevelandfilm.org/films/2016/morris-from-america

Topics: Migration, Race

PARISIENNE (Peur de rien)

Year: 2015

Country: FRANCE

Run Time: 119 minutes

http://www.clevelandfilm.org/films/2016/parisienne

Topics: Migration

BABAI

Year: 2015

Country: GERMANY, KOSOVO, MACEDONIA, FRANCE

Run Time: 104 minutes

http://www.clevelandfilm.org/films/2016/babai

Topics: Kosovo

ENCLAVE

Year: 2015

Country: GERMANY, SERBIA

Run Time: 92 minutes

http://www.clevelandfilm.org/films/2016/enclave

Topics: Kosovo

THE FENCER (Miekkailija)

Year: 2015

Country: FINLAND, ESTONIA, GERMANY

Run Time: 99 minutes

http://www.clevelandfilm.org/films/2016/the-fencer

Topics: Soviet Union, Cold War

HEIL

Year: 2015

Country: GERMANY

Run Time: 104 minutes

http://www.clevelandfilm.org/films/2016/heil

Topics: Germany, Neo-Nazi

WINNETOU’S SON (Winnetous Sohn)

Year: 2015

Country: GERMANY

Run Time: 92 minutes

http://www.clevelandfilm.org/films/2016/winnetous-son

Topics: Karl May, Germany

EVERY FACE HAS A NAME

Year: 2015

Country: SWEDEN

Run Time: 73 minutes

http://www.clevelandfilm.org/films/2016/every-face-has-a-name

Topics: Migration, Sweden, World War II